Three things I learned from yoga that may help me survive the final year of the PhD

By Jennifer Gresham

I.

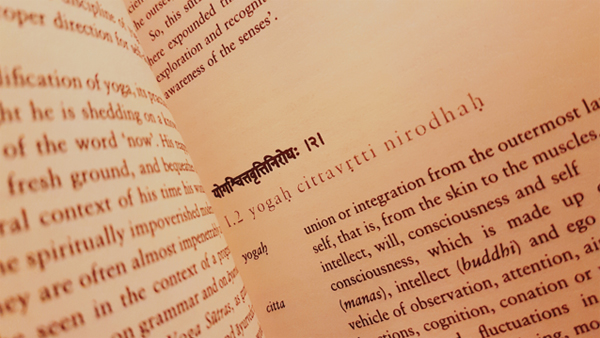

yogas citta vritti nirodah

Patañjali, Yoga Sutras (c. 400 CE)

“Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of the mind.” (Trans. Edwin F. Bryant)

“Yoga is the cessation of movements in consciousness.” (Trans. B.K.S. Iyengar)

“Yoga is the ability to direct the mind exclusively toward an object and sustain that direction without any distractions.” (Trans. T.K.V. Desikachar)

This is the second aphorism or sutra of the first chapter of Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras and the sage’s definition of yoga, one that foregrounds the mental (as in those things relating to consciousness) rather than physical aspects of the practice—or raja rather than hatha yoga. While neither the most elegant nor the most concise—nor even, perhaps, the most accurate—of the above three translations, Desikachar’s is the one I like the best, the one that has been most useful to me in thinking about and planning for my final year of doctoral work. It is the translation of a trained engineer, which may account for the way it seems to lend itself quite easily to practical, everyday application, and it is also the translation of a son and student of Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, often identified as the founder of modern yoga, with whom Desikachar studied the sutras in a process that would take them through the text together seven times. Desikachar’s translation suggests that there is not as much distance between my present yoga practice and the dissertation I will have to complete within the next twelve months as one might at first assume; that all I have learned by practicing asanas (postures) on my yoga mat can be used toward other ends; that I should cultivate focus and control distractions; and that writing my dissertation might itself, in a way, be a form of yoga. “A further meaning of the word yoga,” writes Desikachar, “is ‘to attain what was previously unattainable.’ The starting point for this thought is that there is something that we are today unable to do; when we find the means for bringing that desire into action, that step is yoga.” These words from The Heart of Yoga form the mantra of my final year.

II.

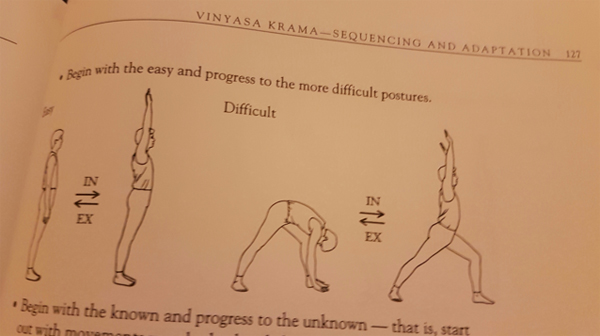

vinyasa krama

Though the term vinyasa was vaguely familiar to me even before I started practicing yoga, I could not then have told you what it meant. Now I know that it often seems to refer to a type of yoga in which each asana or posture flows into the next in coordination with breath, though it should be noted that such categories and types of yoga seem to increasingly reflect both yoga’s commercialization and globalization as opposed to more traditional divisions of practice. In my readings thus far, it is the concept of vinyasa krama—rather than a specific kind or type of yoga designated as vinyasa—that frequently appears in literature on the subject to denote a general principle of structuring the sequence of asanas in physical practice. In The Heart of Yoga, Desikachar tells us that “[k]rama is the step, nyāsa means ‘to place,’ and the prefix vi– translates as ‘in a special way.’” Vinyasa krama involves a series or progression of ordered steps incorporating posture and counter-posture, inhalation and exhalation, transitions and holds—all designed and put together toward achieving a certain aim or purpose. It also seems to refer to the way learning can take place within the framework of one’s practice as a whole. A.G. Mohan—who, like both T.K.V. Desikachar and B.K.S. Iyengar, was a student of Krishnamacharya—calls vinyasa krama an art. My teachers in Hong Kong—for whose excellent instruction I will always remain grateful—seem to deploy this in all of their classes, whether they be identified as hatha, yin, power, or flow. Vinyasa krama is a useful way of looking at the work that has already and will go into writing the dissertation, which is likely why those who have successfully completed their PhDs so often talk about doctoral work and thesis writing as a particular kind of process.

III.

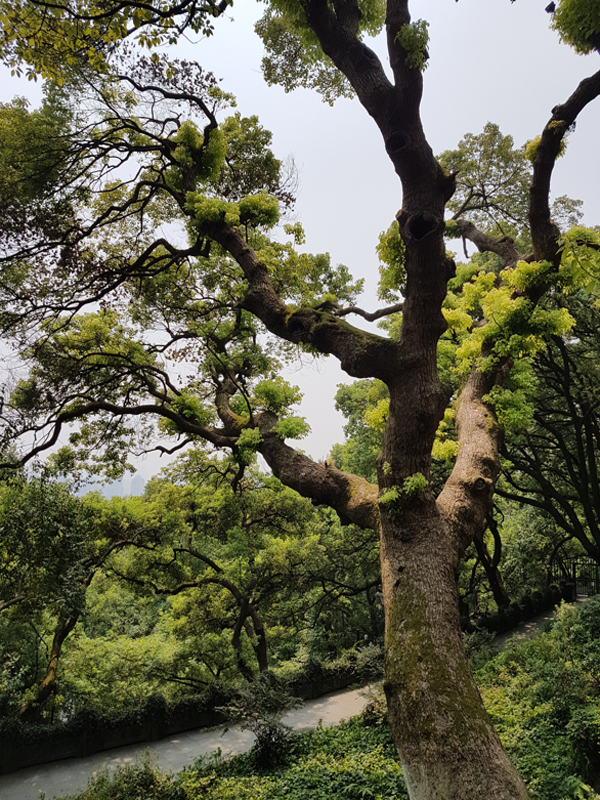

vrksasana

I had seen the image of this asana countless times before my first yoga lesson. Television commercials. MTR ads. Lululemon shopping bags. Facebook. Now I know it as vrksa (tree) + asana (posture). In this asymmetrical standing posture physical balance is achieved by mental focus. The asana is not particularly difficult to perform, but it can be surprisingly hard to hold under certain conditions (in a crowded classroom; when combined with a forward bend; with one’s eyes closed). Its beauty lies not only in its effect—in which the relaxed steadiness (sukha and sthira) characterizing all properly executed asanas produces a sense of well-being—but also in the way it branches into other balancing postures as a link in a chain of movement. Vrksasana into utthita hasta padangustasana. Vrksasana into natarajasana. A room full of students performing vrksasana is always aesthetic. A forest. A statuary. B.K.S. Iyengar writes that mastering asanas leads to the disappearance of dualities. When balancing comfortably in vrksasana I feel like I can begin to have a sense of what this means. It is not unlike a certain state that can be achieved in the process of writing. Vrksasana is a reminder of the calm, clear stillness that can accompany states of heightened focus and attention. I must always bear this in mind when preparing to write: this state of consciousness is one I should welcome rather than fear.

Namaste.

Images:

- Photo of the building where I had my first yoga lesson in April and where I still attend classes every week (Sheung Wan, Hong Kong).

- Photo of B.K.S. Iyengar’s book, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali (Thornsons, 2002).

- Photo of A.G. Mohan’s book, Yoga for Body, Breath, and Mind (Shambhala, 2002)

- Photo of Google image search results for vrksasana.

- Photo of tree on Mount Wu, Hangzhou, where I attended a yoga class at Yoga Summit.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.