The Significance of the Fiesta

by Aaron Anfinson

Last summer I found myself at a flea market in Barcelona, sifting through hundred-year-old books written in a language that, for me, was completely new. Focused on what I could understand: the publication dates, I was immediately fixated on an inconsequential challenge to determine the oldest text. As I excitedly examined a book written just a century and a half after the 1714 fall of Barcelona, it was snatched from my hands—taken away by Algerian merchants navigating a floral loveseat sofa and its occupant, a shoeless girl in a dusty lampshade hat, across the room. Soon, everything was uprooted; towers of books formed uneven stacks in the back of the market, cairns marking the far corners of the room.

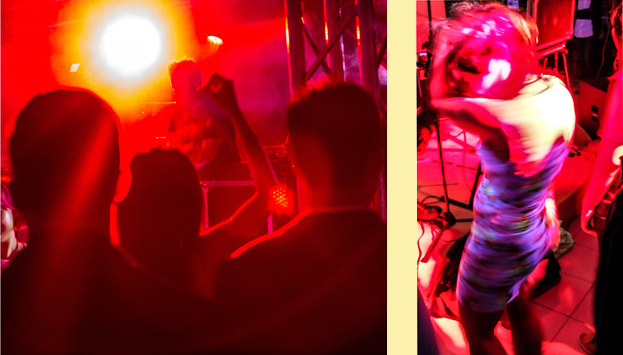

Loiterers like myself (nobody seemed keen to purchase anything) looked even more lost than usual. Causing anticipation to overcome bewilderment, a table unfolded with speakers poorly fixed to each leaf. The floor, having been just cleared of merchandise, was soon filled with cheers and remixes cut and served from a dining room tabletop. It was a spontaneous fiesta, a cover-charge-free democratisation of dance administered by a fervour of feelings for Catalan independence.

The fiesta, I would later discover, is so much more than a party or celebration; it’s the merging of participants and spectators in convention-breaking performances of the carnivalesque. Fostered during one of the longest authoritarian dictatorships of the twentieth century, the fiesta became a component of free expression that contributed to the shattering of many taboos constructed under the Franco regime. Events like this flash fiesta are spaces of escapism that allowed for the imagining of an alternative.

These imagined alternatives, the counterculture movements that flourished after Franco’s death, have been and still are portrayed in degrees of hedonism and as adjustments to consumerism. In an exhibit at the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, for instance, musician Nacho Vegas echoes others in stating that the post-Franco alternatives weren’t political—at least not like the anti-Thatcher and anti-Reagan tendencies of Anglophone punk.

Yet, in the face of roughly three centuries of varying degrees of linguistic, cultural and political sanctions, the Catalan region has grown into an autonomous community of Spain, a community seeking independence. In spite of Barcelona’s commercialisation of pleasure and hedonism at a set price, this independence carried over into a fiesta, a milieu of growth expanding with each newly recruited passer-by. The significance of this fleeting space of free expression has much more dynamic implications, allowing for the consideration of a new order of things.

Therefore, if only for a brief moment last summer, I found myself at a spontaneous fiesta in a free Catalonia. Standing in the middle of a makeshift dance floor, I thought of Hong Kong and these next few years. Still today, that particular fiesta (my first) reminds me of the importance of breaking with routine, of making space for new possibilities to influence the everyday. I can’t help but wonder what Hong Kong’s fiesta might look like.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.