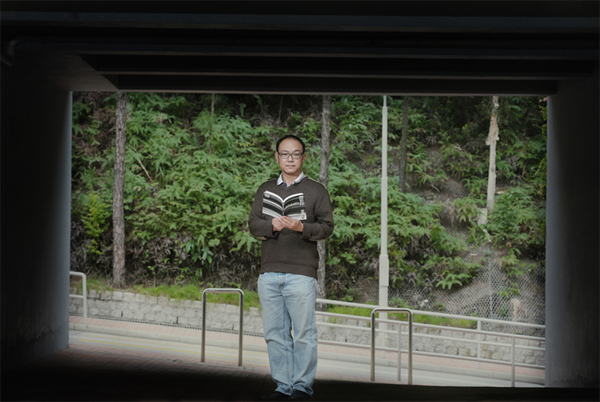

An Interview with Eddie Tay

Words by Huiwen Shi and Eddie Tay. Photography by Keith Hiro.

After completing his Ph.D. at The University of Hong Kong, Eddie Tay began his academic career at the English Department of Chinese University of Hong Kong, where he teaches courses on Children’s Literature, Reading Poetry and Creative Writing. Professor Tay has published widely both critically and creatively. Both HKU Press and NUS Press published his book on Singaporean and Malaysian literature in 2011. And in his three poetry collections (Remnants (2001), A Lover’s Soliloquy (2005) and The Mental Life of Cities (2012)), one gets to see a more personal, sensitive and retrospective Eddie. Active in the local creative scene, he is also an editor for Cha: An Asian Literary Journal.

To know more about Eddie, please see the following webpage:

http://www.eng.cuhk.edu.hk/eng/about/academic_staff_detail/12

~

Can you tell us something about your undergraduate training at NUS? How does it help to shape your poetry?

I took Edwin Thumboo’s year-long creative writing course, and he introduced me to many writers in the region. I got to meet writers like Shirley Lim (who was subsequently the head of English at HKU for a period of time) as well as Wong Phui Nam. It was then that I began to understand literature as a contemporary, living phenomenon, and that perhaps I might have something to contribute. I guess when I write, I write with a very strong sense of place.

I have learnt a lot from Singaporean poets like Toh Hsien Min, Alvin Pang and Yong Shu Hoong, and so many others. They regard themselves as literary activists, acknowledging that the job of writers is not just to write. Literary “work” involves activities such as organizing poetry readings, maintaining reputable online literary journals (such as QLRS) and creating public awareness of the significance of poetry through various other avenues. They align themselves with independent publishers and hold readings at independent bookstores as well as public libraries. The writer has a social role to play in contemporary culture.

Why did you choose to study outside Singapore, and why HKU in particular?

My Ph.D. thesis was about English language literatures in Singapore and Malaysia, and Professor Elaine Ho seemed to me to be the ideal supervisor, given that she was working on English language Hong Kong literature at that time. We have a lot in common in terms of our material and approach to literature. I was interested in simply reading literary works and allowing the works to speak to me and to various debates in the field of postcolonial literary studies.

At the same time, Hong Kong is only a few hours away, so in a sense, I could still keep in touch with what was happening in Singapore’s literary scene.

What are the similarities between NUS and HKU? Do they tell us anything about Singapore and Hong Kong?

I remember feeling a bit strange in that there wasn’t any sense of cultural shock at all. From my point of view at least, I understand HKU because it is very much like NUS. Both are very well-organized institutions, and both departments of English take their research and teaching seriously. These are wonderful places for aspiring academics and creative writers.

Singapore and Hong Kong are so similar—that’s why they’re regarded as rivals in many ways in terms of attracting global talent and capital.

What is the most memorable thing about studying at HKU for you?

It’s definitely the Main Building. The general ambience just makes me want to sit down and open up a book immediately. It’s too bad the department is no longer housed in the building.

How did you get involved in the local writing scene? How has it changed over the years?

I was a featured poet at the Inaugural Hong Kong International Literary Festival in 2001, and I read at one of the Poetry OutLoud sessions. I got to meet Dave McKirdy, Martin Alexander and Madeleine Slavick. We kept in touch, and when I started on my Ph.D. in 2003, I hung out with them quite a bit.

The people have changed. Some of them left Hong Kong, and there are new people now. The fact is that I have also changed over the years. Regretfully, now that I am a family man with two young kids, I can’t spend as much time hanging out with my fellow writers as much as I want to.

How do you think about the creative writing in HK? In both English and Chinese?

Obviously there’re more avenues for Chinese language writing simply because of Hong Kong’s demographic. But there’s definitely room for English language writing too, given that Hong Kong is after all, a pretty cosmopolitan place.

How do you approach creative writing as a poet and critical writing as an academic? Any difficulties? Any advice for aspiring young poets?

This is an ongoing process, and I’m exploring how one could do academic research as a creative writer. I’m constantly seeking a balance, I suppose. The scholar in me tells me I need to be rigorous with my conceptual engagements, and the poet in me tells me I have to be open to the flow of writing so that it takes me to a place that cannot be fully determined at the start of every writing project.

I confess I don’t fully know what I’m doing most of the time. My approach to writing? I struggle and struggle and suddenly, I have a poem/journal article/book chapter. My advice to young poets: be patient and stay with the struggle.

Your adaptation of Chinese classical poetry in the first two collections is extremely fascinating. You did not do any conventional translation. Instead, you used the imagery of the classical poets and invented your own versions. Will you continue to revisit the Chinese canonical works as a source of your inspiration?

I think of my “translations” as really a dialogue with the masters. I learn from them and try to make sense of what they have done using my own language. Will I do that again? Yes, definitely. There’s so much to learn.

How does the Chinese language influence your English writing? In The Mental Life of Cities, there are quite a few poems with a juxtaposition of English and Chinese. Is that your new project? To mix up the two languages?

Yes, that’s my way of doing justice to the languages that surround me. I try to work with counterpoints, pitting the rhythm of one language against another.

I know that you are currently working on a project to do with street photography and poetry. How does it work? How do the streets of Hong Kong inspire you?

I suppose I try to do something different with every book. You could read different poems, but sometimes you get the sense that they emerge from the same playbook, so to speak. I seek to change the playbook itself in my writing. Now, I’m fascinated by the relationship between photography and language.

Street photography came naturally out of my interest in film cameras. I currently run a blog called Hong Kong Lucida which features street photography. The blog is in turn affiliated with Cha, an online literary journal on which I serve as Reviews Editor. I find myself fascinated by social media and its implications for scholarship, creative writing and photography.

Do you have any advice for current PhD students at HKU? Any tips on becoming a good creative/academic writer?

Stay with the struggle.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.