Taking Pictures

By Aaron Anfinson

We all take pictures. At some level, we’re all photographers. More than ever, we’re increasingly noticing light and framing our lives in mobile-phone square formats, self-promoting Facebook profile pictures, vacation snapshot souvenirs and even the first triumphs of children that have seemingly grown while we weren’t looking. We’re all “taking pictures,” frozen, divided seconds that allow us to ponder the moment that just escaped, hopefully making living our lives that much more intense.

There’s something unique and powerful to both the process and interpretation of a single image. We record video but “take” pictures. Photography involves something more: a direct focus on a “micro-moment” and an interaction, both during and after the photo is taken. For me, photography and this interaction has allowed room for reflections while living abroad. Depending upon the local traditions, I discovered that the act of taking photos can mean very different things.

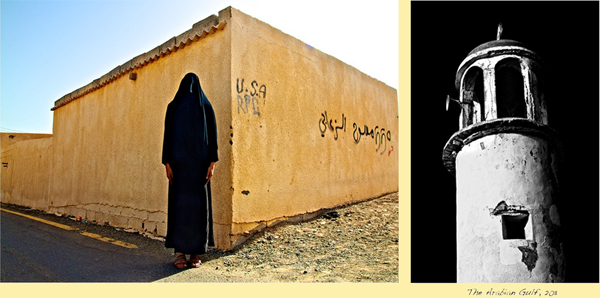

This was especially true in the Arabian Gulf where, despite globalization and a whole region in an exciting transition, tribal influence and a real sense of strong and sometimes controversial tradition remains. In small Bedouin villages, personal privacy pours over into public space. Social conduct is culturally regulated and social media is often debated and condemned. People, therefore, can be especially wary of photography. Cameras have often been restricted to the perception of being rather serious tools, wielded and unsheathed only at appropriate events and used carefully, specifically along gender lines. “Taking pictures” outside these unwritten rules could be reacted to like stealing. For me, photography and this interaction often involved only very controlled, familiar subjects in very explicit, staged and posed moments. Photos weren’t taken as much as they were made.

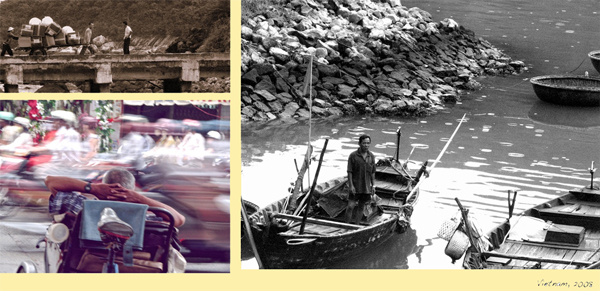

Living in rural Vietnam, however, the interaction was much more open, but, at the same time, somewhat undervalued. With rapid new industrialization and consumerism after the devastation of war, Vietnam has arguably undergone some of the world’s most drastic changes. People’s perception of a large camera too seems to reflect this. Sure, an outsider with a camera automatically fits into a snap-happy tourist stereotype, but there seems to be more to it. There seems to be an overall millennial-style grasp of photography as an optimistic personal expression of the present with everyone enthusiastically leaning toward some imagined technological future. Accompanying this optimism is, of course, the hangover of the usual chaos and frustration following dramatic change and the unfulfilled promises of wealth and relaxation that such modernization supposedly entailed for all. Photography in this exchange was trapped somewhere in the middle.

In a complete contrast, rural Midwestern America seems to have an overwhelming propensity for nostalgia. Whenever I visit “home,” I get the feeling of one foot entrenched in the past, one foot in the present, and perhaps a reluctant wave toward the future. The past is valued and reflected upon, sometimes even re-imagined. I can’t help but notice that much of my photography in the Midwest is unwillingly nostalgic for the frontier. From Native American Pow Wow celebrations to rodeos, people work hard at keeping traditions alive. From the rediscovery of their late grandmothers’ home cooked recipes to young people relearning how to preserve garden vegetables for the winter, there is a vintage revival. Photography often acts as the medium of the reenactment, embraced and traditional.

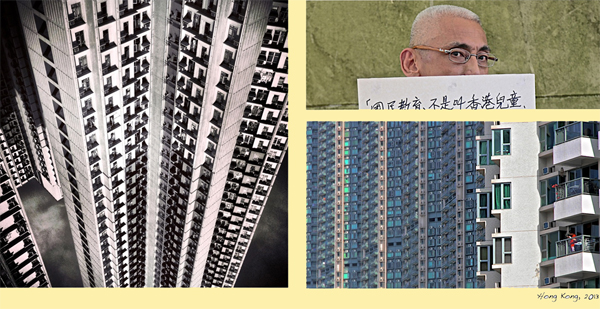

Overall, I’ve learned and relearned that “taking” photos is so much more that just the documentation of an event. Photography involves an underlying power structure, a vulnerability to being in a photograph that means different things in different societies. Photos also can reveal a small, frozen slice of local life at a fraction of a second. Perhaps that’s why photography equipment is for sale on nearly every Hong Kong corner. We have a wonderful, constantly changing cityscape just outside our front door. Photography may be the perfect reflective break from it all, changing our daily routine and even forcing us to catch our breath and recognize the beauty around us. Just don’t forget to take pictures.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.